Scientists develop artificial 'biospleen'

14 Sep 2014

Novel blood-cleansing device inspired by the human spleen is designed to filter bacteria, fungi and toxins.

A team of scientists from Harvard University’s Wyss Institute has engineered an artificial spleen as a means of more effectively treating sepsis.

Sepsis, commonly known as blood poisoning, causes the body’s immune system to go into overdrive, which instigates a series of reactions including widespread inflammation, swelling and blood clotting.

“We didn’t have to kill the pathogens. We just captured and removed them

Wyss Institute scientist Mike Super

According to researchers, current methods for treating sepsis are ineffective as patients with the disease die in around 30% of diagnosed cases.

Unfortunately, identifying the specific pathogen responsible for sepsis can take several days, and in most patients the causative agent is never identified. The prescription of antibiotics can often have little effect on the sepsis, and can cause devastating side-effects, the researchers said.

Fortunately, the artificial device, dubbed the ’biospleen’, has exceeded expectations with its ability to cleanse human blood tested in the laboratory, and has dramatically increased survival rates in animal tests to around 90%.

According to research, the biospleen has the ability to filter live and dead pathogens from the blood in a matter of hours, as well as dangerous toxins that are released from the pathogens.

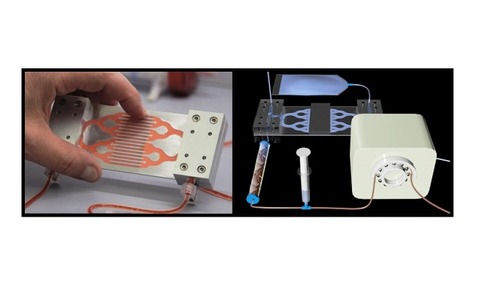

The biospleen is a microfluidic device that consists of two adjacent hollow channels that are connected to each other by a series of slits: one channel contains flowing blood, and the other has a saline solution that collects and removes the pathogens that travel through the slits.

Vital to the success of the device are tiny nanometre-sized magnetic beads that are coated with a genetically engineered version of a natural immune system protein called mannose binding lectin (MBL).

The device was initially tested on human blood that had been deliberately spiked with a number of pathogens.

Results proved that the team was able to filter blood in a far more efficient manner than previously possible, and the nano-magnets pulled the beads - coated with the pathogens - out of the blood.

Building on this success, the team then tested the device using rats that were infected with E. coli, S. aureus, and toxins - mimicking many of the bloodstream infections that human sepsis patients experience.

Similar to the tests on human blood, after just five hours of filtering, about 90% of the bacteria and toxin were removed from the rats’ bloodstream.

“We didn’t have to kill the pathogens. We just captured and removed them,” said senior staff scientist at the Wyss Institute Mike Super.

Likewise, Wyss Institute founding director Don Ingber said: “Sepsis is a major medical threat, which is increasing because of antibiotic resistance. We’re excited by the biospleen because it potentially provides a way to treat patients quickly without having to wait days to identify the source of infection, and it works equally well with antibiotic-resistant organisms.

“We hope to move this towards human testing to advancing to large animal studies as quickly as possible.”

A full account of the study has been published in the journal Nature Medicine.