Fighting Ebola first-hand

4 Dec 2014

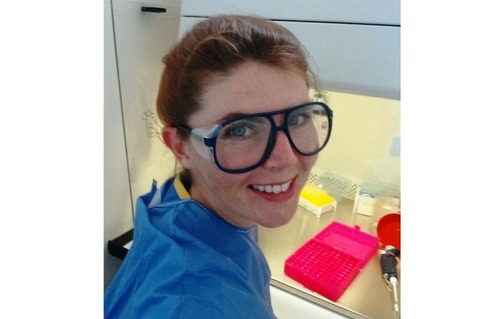

Armed with clinical diagnostics expertise and vital information on the treatment of exotic pathogens, UWE postgraduate Laura Holding discusses the spread of Ebola, and how her lab in Sierra Leone is helping to stop it.

My course at UWE (The University of the West of England) was MSc Medical Microbiology, which was really useful to me in coming here, as my normal job is in a food, water and environmental lab.

It gave me a good knowledge of clinical diagnostics as well as information on the epidemiology, transmission, diagnosis and treatment of exotic pathogens.

“The earlier people receive treatment the better chance they have of survival

Laura Holding

Like most of my colleagues here, I wanted to use my training and education to help a genuine cause.

A typical day involves setting up the lab and cleaning all surfaces with a very strong bleach solution and ensuring we have enough disinfectants, consumables and reagents for the day.

We also run through safety checks.

There are five people in at any one time and we rotate between duties such as isolator work, RNA extraction and PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction), although this depends on the experience and expertise of each person and how many samples there are.

We receive samples from the Ebola Treatment Centre and also larger collections from the community.

[Unfortunately], samples don’t always come in a uniform manner, so it can take time in the heat to sort through and check that they are in a safe condition to process.

After they are checked they are then taken into the flexible film isolator to be inactivated and prepared to perform PCR on.

Results are validated and reported in as little as four hours depending on batch size.

It’s important to get the results out fast so that positive patients can be treated as quickly as possible and negative patients can be released back to their families and away from any infectious patients.

The earlier people receive treatment the better chance they have of survival.

Understanding Ebola

It’s important not to create panic through the media, which can impact on the crisis response, for example, the threat of quarantine for returning volunteers may deter others wanting to help.

The risk to the general UK population is very low and we have a world class healthcare system in place to deal with any isolated cases.

Although it is highly infectious, the simple precautions you can take reduce the risk greatly.

The original version of this interview first appeared on the UWE alumni website.